In the article under review, a professor from the SDA Theological Seminary at Andrews University examines the Christian debate over slavery in nineteenth-century America, and how different approaches to Biblical authority allegedly led to different conclusions.

Read MoreWilliam Wilberforce and the slave trade

William Wilberforce (1759-1833) was the grandson of a British merchant who had made his fortune trading with the Baltic nations. William's father died when William was nine, and his temporarily overwhelmed mother sent him to live with an aunt and uncle who were Methodists. At the age of 17, William was sent to study at Cambridge, and the deaths of his grandfather and uncle in the next couple of years left him independently wealthy while still a teenager.

In those days, wealthy gentlemen students pursued cards, drinking and theater more avidly than studies, and young Wilberforce was no exception. He excelled socially, however, and became friends with William Pitt, the younger, who was to become prime minister just a few years later (at age 24!) and who talked Wilberforce into a career in politics. Wilberforce stood for parliament at age 20, while still at Cambridge, and obtained his seat, as was the custom, by spending a princely sum of money buying votes. His political career did not impinge on his primary activities of cards, drinking and socializing in circles appropriate to a man of his standing. The influential salon hostess Germaine de Staël called Wilberforce “the wittiest man in England,” and he must have had a fine singing voice, as Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, remarked that the Prince of Wales would go anywhere to hear Wilberforce sing.

William Wilberforce (1759-1833) was the grandson of a British merchant who had made his fortune trading with the Baltic nations. William's father died when William was nine, and his temporarily overwhelmed mother sent him to live with an aunt and uncle who were Methodists. At the age of 17, William was sent to study at Cambridge, and the deaths of his grandfather and uncle in the next couple of years left him independently wealthy while still a teenager.

In those days, wealthy gentlemen students pursued cards, drinking and theater more avidly than studies, and young Wilberforce was no exception. He excelled socially, however, and became friends with William Pitt, the younger, who was to become prime minister just a few years later (at age 24!) and who talked Wilberforce into a career in politics. Wilberforce stood for parliament at age 20, while still at Cambridge, and obtained his seat, as was the custom, by spending a princely sum of money buying votes. His political career did not impinge on his primary activities of cards, drinking and socializing in circles appropriate to a man of his standing. The influential salon hostess Germaine de Staël called Wilberforce “the wittiest man in England,” and he must have had a fine singing voice, as Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, remarked that the Prince of Wales would go anywhere to hear Wilberforce sing.

In 1785, while on a tour of the European continent, Wilberforce read, “The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul” by a leading non-conformist minister, Philip Doddridge. He resolved to give his life to Christ. He began to rise early in the morning to pray and study the Bible, and he began keeping a journal. The upper classes of Wilberforce's England considered religious fervor a faux pas, and stigmatized it. Wilberforce wondered if he should even continue in public life, and sought advice from John Newton, a former slaver and the author of the hymn “Amazing Grace.” Both Newton and William Pitt advised Wilberforce to remain in parliament and allow his religious convictions to inform his legislative work.

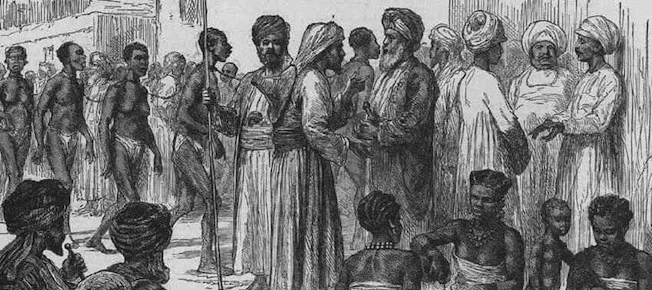

In the previous article, we saw how slavery gradually withered away in Christendom and was replaced by the feudal system. Unfortunately, a few centuries later the nations of Christendom became involved with slavery in the “New World.” It soon became apparent to the Spanish, Portuguese, French, English and Dutch colonizers of the Americas and “West Indies” that the best opportunity for gain came from growing sugar cane and other warm weather crops not grown in Europe. It was believed that Africans would be best suited to the back-breaking labor necessary to operate the plantations, and more resistant to the tropical diseases that took a heavy toll on Europeans. Slavery was well established in Africa; the Islamic ummah had been buying African slaves for several centuries. Europeans found many localities, especially in West Africa, where they could purchase slaves from African slave-dealers. A triangular trade route developed in which British ships took manufactured goods from Britain to Africa to be traded for slaves, then delivered the slaves from Africa to the West Indies for sale to plantation owners—the infamous “middle passage” of the triangular route—and finally delivered sugar, rum, molasses, or tobacco from the Americas and West Indies to Europe. This terrible triangular traffic was to continue for centuries.

By the late 18th Century, the stark inhumanity of the trans-Atlantic slave traffic was becoming widely known. In 1787, many of the drafters of the United States Constitution wanted to outlaw the traffic, but southern slave-holding interests negotiated a compromise which postponed any ban until 1808, at the earliest. (Article 1, section 9) On March 2, 1807, congress passed a bill that was signed into law the next day by President Thomas Jefferson (a southerner and slave owner) forbidding the importation of slaves into the United States, effective January 1, 1808, the first constitutionally permissible date. The disdain for the slave traffic was so great, however, that by 1808 every state except South Carolina had already banned the importation of slaves.

The year 1787 marks the beginning of William Wilberforce's campaign to outlaw the slave traffic in the British Empire. He wrote in his journal, “God almighty has set before me . . . the suppression of the slave trade.” He met with Thomas Clarkson, a Christian abolitionist who had been studying and researching the slave trade for many years, and who was to provide the witnesses and other evidence supporting Wilberforce's legislative efforts. Wilberforce met with the newly formed “Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade,” a group of Quakers and like-minded abolitionist Anglicans. He met with Prime Minister William Pitt and future Prime Minister William Grenville, and both encouraged him to introduce a bill banning the slave trade. In 1788, however, Wilberforce became seriously ill and had to leave London to convalesce at Bath. During his absence, Pitt ordered the privy council to investigate the slave trade and report to parliament. In 1789, a recovered Wilberforce gave his first major speech against the slave trade, and introduced his first anti-slave trade bill. Opponents sidelined the bill with two years of absurdly drawn out hearings, after which the bill was defeated, 163 to 88.

Wilberforce would annually re-introduce the anti-slave trade bill every year through 1799. In 1793, his measure failed by only 8 votes, but the radical phase of the French Revolution and war between Britain and France put the cause on the back burner. In 1796, the measure failed by only 4 votes; at least six abolitionist members chose that day to see a new Italian comic opera playing in London. Wilberforce wrote in his diary: “Enough at the Opera to have carried it. I am permanently hurt about the Slave Trade.”

William's lack of success in ending the slave trade was ameliorated by happiness in his personal life. In 1797, Wilberforce was introduced to Barbara Ann Spooner as a possible wife. Wilberforce was instantly infatuated, and proposed marriage only 8 days later. The couple were married six weeks later, and had six children over the next 10 years.

In 1804, Wilberforce introduced his bill for the first time since 1799; this time it passed the House of Commons but died in the House of Lords, as Wilberforce mistakenly trusted men not as committed to the cause as he was. Thanks to constant, unflagging efforts of Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and many other Christian activists, the slave trade was a prominent issue in the Parliamentary election of 1806, which returned a good number of abolitionists to the House of Commons. In 1807, Lord Grenville introduced the anti-slave trade bill, it again passed the House of Commons, and Grenville guided it through the House of Lords, which approved it and returned it to Commons for final passage. On February 23, 1807, after many members of parliament rose to speak and salute Wilberforce's tireless efforts, the bill to ban the slave trade was overwhelmingly passed, 283 to 16. Wilberforce's face streamed with tears as the final tally was taken.

After at last winning the two-decades-long fight to ban the slave traffic, Wilberforce did not immediately call for abolition of slavery, feeling that the slaves were ill-prepared to fend for themselves. In 1816, however, Wilberforce began to denounce slavery itself. In 1823, Wilberforce at last lent his considerable prestige to the cause of total abolition of slavery within the British Empire. He published a tract entitled, “Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies.” In June 1824, Wilberforce gave his last speech in Parliament, calling for the abolition of slavery. Declining health forced his resignation from Parliament in 1825, although he continue to be active in the anti-slavery movement. The bill to abolish slavery in the empire passed one month after Wilberforce's death on July 29, 1833; he died knowing it would pass. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, near his good friend William Pitt.

Christianity was the animating force behind the movement to abolish the slave trade, and also behind the incomparable career of William Wilberforce. “A man who acts from the principles I profess,” he said, “reflects that he is to give an account of his political conduct at the judgment seat of Christ.”

Slavery and the Bible (Part III)

We've seen that the New Testament writers, most notably Paul, did not directly attack the institution of slavery. Paul advised slaves to obey their masters, to work conscientiously even when unsupervised (Eph. 6:5-8; Col. 3:22-23), to be trustworthy and not steal the master's property (Tit. 2:9), and to think of and emulate Christ when suffering unjustly (1 Pet. 2:18-23). Masters were admonished to treat their slaves justly and not to threaten them, but to recognize that in God's eyes the slave was as valuable as his master (Eph. 6:9; Col. 4:1; Col. 3:11; Gal. 3:28).

We've also seen how this advice was applied in the case of Onesimus, a slave in what is now Turkey, who stole money from his master, ran away to Rome, was converted to Christianity, and became a helper to Paul. Paul sent Onesimus back to his master, Philemon (who was also a Christian whom Paul had converted), bearing a letter telling Philemon to treat Onesimus just as he would treat a son of Paul. Philemon was to think of Onesimus not as having run away but as having gone on a Christian mission in Philemon’s stead, to treat him not as a slave but as a brother, and not even to mention the money he had stolen when he ran away. In effect, Paul had replaced Roman law and custom relating to slavery with a new standard of Christian behavior.

We've seen that the New Testament writers, most notably Paul, did not directly attack the institution of slavery. Paul advised slaves to obey their masters, to work conscientiously even when unsupervised (Eph. 6:5-8; Col. 3:22-23), to be trustworthy and not steal the master's property (Tit. 2:9), and to think of and emulate Christ when suffering unjustly (1 Pet. 2:18-23). Masters were admonished to treat their slaves justly and not to threaten them, but to recognize that in God's eyes the slave was as valuable as his master (Eph. 6:9; Col. 4:1; Col. 3:11; Gal. 3:28).

We've also seen how this advice was applied in the case of Onesimus, a slave in what is now Turkey, who stole money from his master, ran away to Rome, was converted to Christianity, and became a helper to Paul. Paul sent Onesimus back to his master, Philemon (who was also a Christian whom Paul had converted), bearing a letter telling Philemon to treat Onesimus just as he would treat a son of Paul. Philemon was to think of Onesimus not as having run away but as having gone on a Christian mission in Philemon’s stead, to treat him not as a slave but as a brother, and not even to mention the money he had stolen when he ran away. In effect, Paul had replaced Roman law and custom relating to slavery with a new standard of Christian behavior.

We have little extra-biblical, historical evidence for how Christians related to slavery, but what there is is interesting and instructive.

Paul tells free Christians that although they are Christ's slaves, they were bought with a price and are not to become slaves of other men. (1 Cor. 7:21-23) But Paul's advice was early ignored, albeit for good causes; Clement of Rome writes (c. 96 AD) that, “We know many among ourselves who have given themselves up to slavery, in order that they could ransom others. Many others have surrendered themselves to slavery, so that with the price that they received for themselves, they might provide food for others.” Some Christians were selling themselves into slavery in order to free others or provide for the needs of others.

We also have evidence that the church sometimes used its funds to purchase freedom for slaves. This is hinted at in an early Second Century letter from Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, to Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna. It is stated more clearly, some centuries later, in the Apostolic Constitutions (c. 390 AD) which provide that, “As for such sums of money as are collected from them in the aforesaid manner, designate them to be used for the redemption of the saints and the deliverance of slaves and captives.”

It had become common by the early 4th century for Christian masters to free their slaves. These religiously motivated manumissions were performed in church in the presence of a bishop. An early ruling of Constantine, made in response to petitions from bishops, refers to slave owners freeing their slaves because of their religious convictions (“religiose mente”). That this was an accepted practice in Constantine's time suggests that it probably began long before then. There was no requirement that Christian masters free their slaves---and certainly not all did---but it is significant that a custom developed pursuant to which (1) Christian masters (2) freed their slaves (3) in a church ceremony (4) before a bishop (5) ultimately with the bishop-requested authority of the emperor.

We also have reports that when extremely wealthy Romans were converted to Christianity, they freed their slaves en masse. When the prefect Hermas was converted by Bishop Alexander during the reign of Trajan (r. 98-117), he was baptized at an Easter festival along with wife, children, and twelve hundred and fifty slaves, to all of whom (the slaves, that is) he gave their freedom plus monetary compensation. In the time of Diocletian (r. 284-305) the prefect Chromatius was baptized with his fourteen hundred slaves whom he also emancipated at the same time, proclaiming that their sonship to God had put an end to their servitude to man. Church historian Phillip Schaff states that, “these legendary traditions may indeed be doubted as to the exact facts in the case, and probably are greatly exaggerated; but they are nevertheless conclusive as the exponents of the spirit which animated the church at that time concerning the duty of Christian masters."

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine why, if the early Christian Church endorsed slavery, it should have (1) used church funds to free slaves, (2) developed a bishop-led church ceremony in which slaves were freed, and (3) encouraged wealthy converts to manumit their slaves en masse. The logical conclusion is that slavery was a pagan institution that the Christian Church did not view as God's ideal form of social organization. But re-organizing society has never been the primary function of Christianity. Christianity changes hearts, and enough changed hearts will eventually lead to a changed society.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, its legal forms and customs, including slavery, gradually fell into disuse and were replaced by what has become known as feudalism, a decentralized system of reciprocal legal and military obligations. By the late Middle Ages slavery had disappeared in Western Europe (although it persisted until much later in parts of Eastern Europe). The slave's feudal counterpart was the peasant who was bound to work specific land and could not move or change his occupation. The peasant's plight bore some similarities to slavery (especially in Russia, where serfs could be bought and sold) but was really a very different kind of institution.

Slavery was unambiguously legitimate in Islam; Muhammad owned slaves, and Muslims consider him the perfect example to emulate. Non-Muslims captured in raiding, piracy, and Jihad warfare were booty; and volumes of Islamic jurisprudence are devoted to regulating the distribution of booty. Although Muslims enslaved millions of black Africans—one common Arabic term for slave, abd or abeed, is also a slang term for a black person---they were equal opportunity slavers and frequently enslaved Europeans, especially from southeastern Europe. Slavery in Muslim lands was typically ended only when they were colonized by the Western powers.

Related articles 1. Slavery and the Bible (Part I) 2. Slavery and the Bible (Part II)

Slavery and the Bible (Part II)

In the Roman world, slavery was a more variegated institution than the African-American slavery we remember. In the empire, there was some debt slavery, some criminals sentenced to slavery, and some people enslaved through piracy and slave-hunting raids, but most slaves were taken in wars of conquest.

Read MoreSlavery and the Bible (Part I)

Unbelievers often point to the failure of the Bible to condemn slavery as a proof that the Bible is uninspired, a merely human, culture-bound product of its times. They reason that a just and loving God would never countenance slavery, much less issue a series of regulations for the operation of such an institution. But what does Scripture actually say, and what type of institution does it regulate?

Read More